by Stella Raine Chu

Volunteers tend to the garden beds at Moore-Jackson Community Garden. Credit: GrowNYC

Volunteers tend to the garden beds at Moore-Jackson Community Garden. Credit: GrowNYCWhat purpose does a community garden serve in a concrete jungle like New York City?

For Elizabeth O’Connor, co-founder of Moore-Jackson Community Garden in Woodside, the answer lies in its namesake: the community.

“Our motto is ‘let’s grow together,’ in more ways than one,” O’Connor said. “Although it’s a garden, this space is now a hub for arts programming, plays, and open mic nights. It’s become the only green space within a ten-block radius.”

Dating back to 1733, Moore-Jackson was originally a burial ground for the English settler Moore family. In 1998, property ownership was transferred to the Queens Historical Society, and in 2019, thanks to the efforts of local volunteers and a non-profit, the garden was established. Since then, the space has grown foods like cucumbers, kale, carrots, sweet potatoes, onions, garlic, eggplant, and a plethora of different types of tomatoes.

O’Connor isn’t the only one who acknowledges the importance of green spaces and community gardens in a city like New York. These gardens have historically provided fresh fruits and vegetables to lower income areas where produce may not be as abundantly available or affordable. In times of famine and food shortages, community gardens filled the gaps in America’s diet. During both World Wars, citizens were encouraged by the U.S. National War Garden Commission to plant “victory gardens” to supplement rations and boost morale.

According to the latest New York State Community Gardens Task Force report, there are about 3,000 community gardens across the state, two-thirds of which are in the five-boroughs. The same report also details a 2010 study which found the benefits of community gardens to be especially prominent among youth populations, where adolescents fostered mutual trust in their peers, particularly those not of the same race as themselves, thus leading to a stronger sense of community.

Moore-Jackson, like most community gardens, is entirely run by volunteers.

“It’s this feeling that you’re doing something together,” says Lena Hunter, a volunteer at the garden. “Even if you have a lot of differences, you still have one similarity: making this garden work.”

Volunteers at Moore-Jackson gather every Saturday at 11:30 a.m. to process food scraps, much of which are dropped off by neighbors in the community. These scraps are then stored away and decomposed to become compost that feed the garden beds. Despite it being the off-season, there’s still a lot of work to be done to maintain the soil.

The carbon that is released from the decomposition process is sequestered and captured in composting, which then makes the gasses viable for plants to use. Once the fruits and vegetables are harvested, they’re given out to volunteers and local food pantries.

“It feels like you’re on a farm. I’m thrilled to be here, it’s a joy to be outside,” said Jessica Coyle, a volunteer at Moore-Jackson of three years. “I’ve made so many friends by just coming here every Saturday, it’s a blast.”

Community gardens aren’t just a way to socialize with neighbors — they have a real impact on health and diet. A study published in the National Library of Medicine found that households that participate in community gardens ate fruits and vegetables around six times a day, while non-participant households only did so around four times a day.

“They’re an opportunity for young people to learn what vegetables look like before they go into a can,” O’Connor said. “It’s so important that kids, and also adults, get their hands dirty, understand where food comes from, and how easy it is to grow it.”

Numerous studies have drawn the correlation between physical and mental health and gardening. It has been found that direct experiences with gardens and green spaces decrease cardiovascular diseases, depression and anxiety symptoms, as well as diabetes and obesity. A combination of physical activity, exposure to sunlight, social interaction and consumption of fruits and vegetables makes community gardens an essential part of any neighborhood.

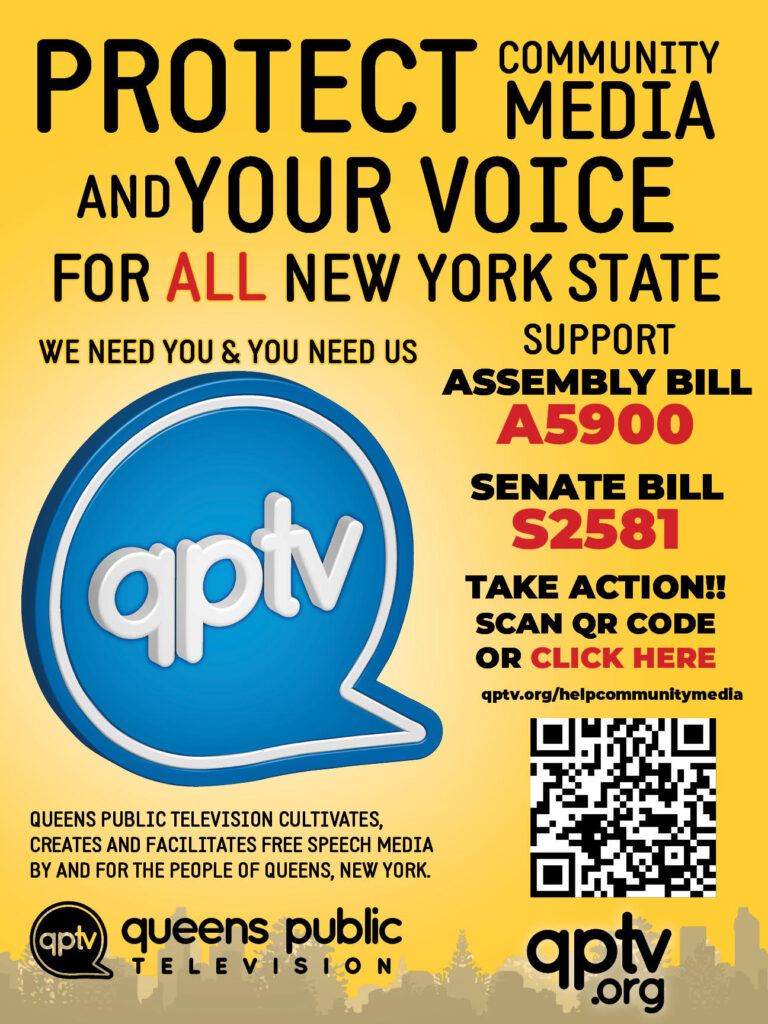

“Gardens can be built in the neighborhood’s image,” said Mike Rezny, associate director of the Green Space program at GrowNYC. The non-profit organization, which built Moore-Jackson, was founded in 1970 with the mission of providing New Yorkers in all five boroughs with fresh, locally grown food and green spaces. The Green Space program, established five years after the organization’s initial founding, has built more than 160 community gardens across the city, providing more than a million square feet of green space for New Yorkers.

“Community gardens are the kinds of places where people can make a direct impact on what their neighborhood looks and feels like,” Rezny said. “You don’t have to be interested in growing vegetables to join a community garden. It’s a great first step of civic engagement.”

Volunteers at Moore-Jackson preparing food scraps for composting. Credit: Stella Raine Chu

Volunteers at Moore-Jackson preparing food scraps for composting. Credit: Stella Raine ChuThe Green Space program works with institutional partners like New York City Parks & Recreation, New York City Housing Authority, and the Department of Education to find potential spaces that might be a good fit to build a garden.

“We’re also looking for strong community partners,” Rezny said. “We want folks that live in the neighborhood to be the ones stewarding and maintaining them, so we want to make sure there’s community support for all the projects we work on.”

Rezny says that Green Space is always looking for new land to build gardens on, even if it means using non-traditional spaces. Potential spaces for building gardens can be submitted through their request form.

Despite community gardens growing in popularity — with 29,000 of them in 100 of America’s largest cities — these urban oases are facing challenges. From lack of funding, inconsistent community engagement, and insufficient space, it isn’t always smooth sailing.

“It’s hard to always deliver on everything,” O’Connor said. While grants — the most common way community gardens receive funding — are helpful and necessary, they often require commitments to certain programming schedules, which isn’t always possible.

Another big issue is inconsistency in volunteers. Because Moore-Jackson is completely volunteer-led, labor retention has become a struggle. O’Connor says that getting the word out about events and volunteer opportunities is a priority for the garden.

Since all events at the garden are held outside, unpredictable weather is a constant issue. Last year, the garden held their 11th annual Play Festival for three weekends in September. It ended up raining all three weekends.

At the start of the growing season, usually late April to early May, the garden hosts a Beautification Day, dedicated to planting new seeds in garden beds. The event is free and open to the public.

Unlike other gardens in the city, Moore-Jackson does not have a waitlist or membership fees — and the garden is truly communal instead of having individualized plots. The fruits and vegetables are planted, grown, and harvested by everyone, to be shared with everyone — instead of each member having their own plot only for them to tend to.

For now, the garden continues to sustain the local Woodside community — providing its neighbors with a lush green space, locally grown produce, and a gathering space open to anyone.

“This is your community garden,” O’Connor said. “It’s not just ours. Everyone’s welcome.”

Carolina Zuniga-Aisa, beekeeper from Island Bee Project in Brooklyn, tends to the honeybees that Moore-Jackson keeps on site. Credit: Stella Raine Chu

Carolina Zuniga-Aisa, beekeeper from Island Bee Project in Brooklyn, tends to the honeybees that Moore-Jackson keeps on site. Credit: Stella Raine Chu

Volunteers tend to the garden beds at Moore-Jackson Community Garden. Credit: GrowNYC

Volunteers tend to the garden beds at Moore-Jackson Community Garden. Credit: GrowNYC Volunteers at Moore-Jackson preparing food scraps for composting. Credit: Stella Raine Chu

Volunteers at Moore-Jackson preparing food scraps for composting. Credit: Stella Raine Chu Carolina Zuniga-Aisa, beekeeper from Island Bee Project in Brooklyn, tends to the honeybees that Moore-Jackson keeps on site. Credit: Stella Raine Chu

Carolina Zuniga-Aisa, beekeeper from Island Bee Project in Brooklyn, tends to the honeybees that Moore-Jackson keeps on site. Credit: Stella Raine Chu