Ruhling: The Woman who takes History to Heart

As a historian, Heather Nicole Lonks Minty is used to telling stories.

Other people’s.

So that’s where we start.

We’re in England, where in 1909 two suffragettes, identified as a Miss Solomon and Miss McLellan, find a novel way to draw attention to the cause.

They mail themselves to the prime minister at No. 10 Downing St. so they can advocate, in person, for the right to vote. (The postal charge is 3 pence, and the “human letters” are unceremoniously returned when the recipient refuses to sign for them.)

Heather starts a new job next month.

“A delivery boy had to actually walk them there,” Heather says, smiling at their audacity and cleverness. “During the mailbox bombing and arson campaign of 1912 through 1914, one woman used to hide explosive devices in her wheelchair.”

In the United States, the women were not so militant. In 1917, they merely chained themselves to the fence around the White House to get President Woodrow Wilson’s attention.

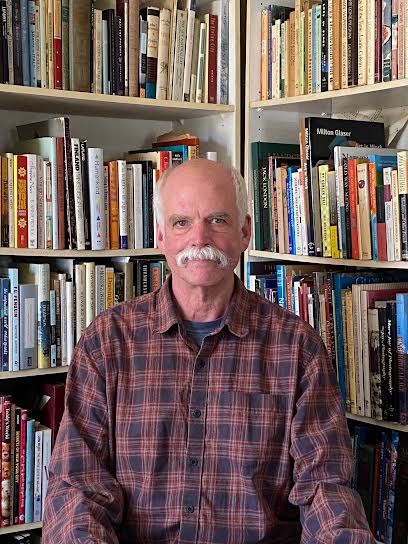

Heather, a tall woman with glamorous gold-rimmed spectacles, tells these and other stories about everyday people to make history come alive.

Whether you’re talking about women picketing to get the right to vote or young men protesting the draft, the stories resonate because “it could be you or someone in your family,” she says.

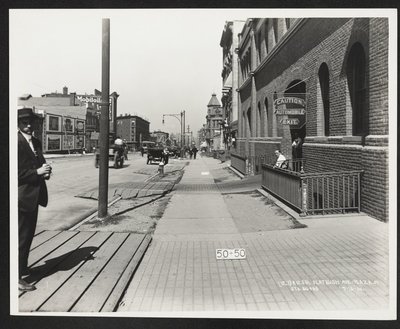

That’s why she finds walking tours so thrilling: You get to stand in a space where history took place.

As far as Heather’s own history, it starts in Flushing, where she was born 32 years ago and where she spent most of her childhood and young adulthood.

At LIU Post, she earned a bachelor’s degree in TV and radio (she loves watching historical documentaries, and her thesis was a video walking tour of the Civil War draft riots) then proceeded to earn a master’s in public history at Royal Holloway, University of London.

“Public history is all about getting history to the public,” she says. “These days, there are many engaging ways to tell stories that are not just exhibitions in museums.”

After returning to New York, she landed a job at the New-York Historical Society, a move that would change her own history in ways she never imagined.

It was there that she met Chris Minty, a “cute” Scotsman fascinated with U.S. history who had a fellowship with the museum.

“We actually were in London at the same time, both frequenting the same research libraries when I was in college, and I did take some day trips to Scotland, but our paths never crossed,” she says.

They were introduced at a staff meeting, but Heather wasn’t impressed enough to pay much attention to him.

It was Tinder that kindled their romance.

“I swiped right, but I still didn’t recognize him,” she says, adding that the people on fellowships like Chris had separate work areas so she never saw him. “He sent me a message saying he thought we worked in the same building.”

Heather thought it was a pickup line until she verified the information.

On Nov. 4, 2014 – Heather, ever the historian, remembers the exact date – they met for coffee.

“Our love of history connected us,” she says. “We spent five hours talking – it’s probably the longest coffee date known to man.”

Their relationship deepened their appreciation not only for each other but also for their respective areas of study.

“He opened my eyes to parts of American history I had never seen before,” Heather says.

Although they had been dating only a couple of weeks, Chris traveled all the way from Morningside Heights to Flushing to have Thanksgiving dinner with Heather and her parents.

“The holiday, of course, is not celebrated in Scotland, so he really didn’t know what he was getting into,” she says. “My mother sent him home with so much food – and he discovered corn bread.”

Heather makes history come alive.

They married and moved themselves and their voluminous collection of history books to Boston, where Chris had been offered a job.

Heather took a position with the Boston Athenaeum and later worked for the Boston Arts Academy Foundation then Respond, whose mission is to end domestic violence.

At the end of 2020, during the pandemic, they returned to New York to be closer to Heather’s family.

Heather was working for Citizens Budget Commission, a nonprofit that focuses on New York City’s and state’s finances and services, when their daughter, Isla, was born.

(For the record, the only reason Isla, who is 6 months old, has not visited a museum yet is because of covid restrictions.)

Next month, after taking a short break in her career, Heather’s starting a new job as the development director of an institute in New Jersey whose mission is gender equality, which syncs with her keen interest in women’s rights.

“Having a daughter makes this even more exciting because instead of fighting only for myself now, I’m fighting for her and her generation,” she says. “That makes it easier for me to leave her and go back to work.”

Nancy A. Ruhling may be reached at Nruhling@gmail.com; @nancyruhling; nruhling on Instagram, nancyruhling.com, astoriacharacters.com.

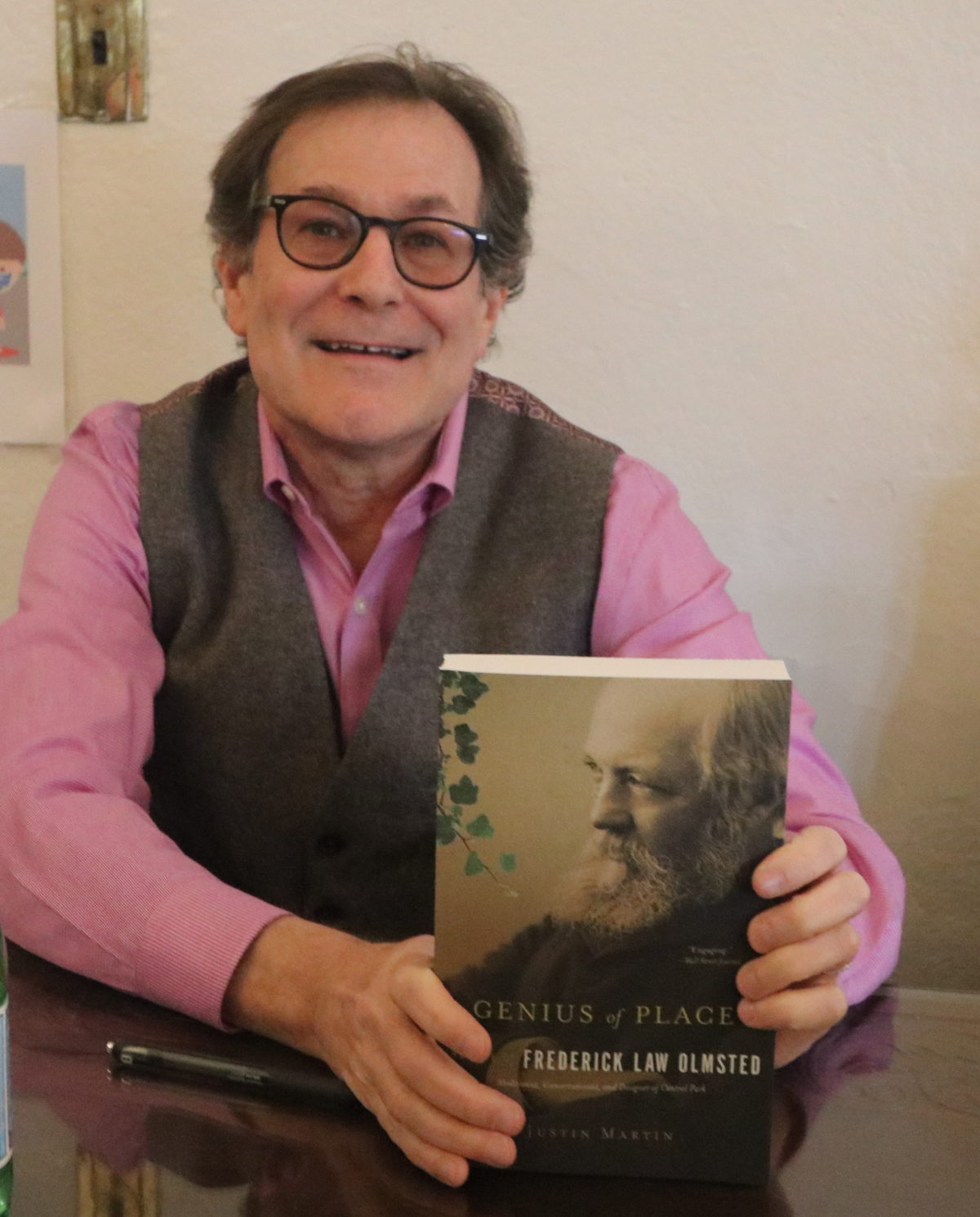

Olmsted was born on April 26, 1822, in Hartford, Ct., and passed away on August 28, 1903, in Belmont, MA. Among his most significant accomplishments are the landscapes of Central Park, Riverside Park and Drive, Prospect Park, Bayard Cutting Arboretum in Long Island, Ocean Parkway and Eastern Parkway, Morningside Park, Downing Park in Newburgh, the U.S. Capitol, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Boston’s Emerald Necklace, and the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina. His son, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr, designed Forest Hills Gardens, along with principal architect Grosvenor Atterbury.

Olmsted was born on April 26, 1822, in Hartford, Ct., and passed away on August 28, 1903, in Belmont, MA. Among his most significant accomplishments are the landscapes of Central Park, Riverside Park and Drive, Prospect Park, Bayard Cutting Arboretum in Long Island, Ocean Parkway and Eastern Parkway, Morningside Park, Downing Park in Newburgh, the U.S. Capitol, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Boston’s Emerald Necklace, and the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina. His son, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr, designed Forest Hills Gardens, along with principal architect Grosvenor Atterbury. That is the site of Olmsted’s farmhouse at 4515 Hylan Boulevard and farm, which was home from 1848 to 1855. Tosomock Farm is where he began experimenting with landscaping and agricultural techniques, resulting in improvements that influenced his later countrywide designs. Today this rare survivor is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is awaiting significant restoration. Martin serves on the board of an organization committed to restoring it. He said, “we are also hoping to open it as a museum dedicated to agriculture and its most famous resident.”

That is the site of Olmsted’s farmhouse at 4515 Hylan Boulevard and farm, which was home from 1848 to 1855. Tosomock Farm is where he began experimenting with landscaping and agricultural techniques, resulting in improvements that influenced his later countrywide designs. Today this rare survivor is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is awaiting significant restoration. Martin serves on the board of an organization committed to restoring it. He said, “we are also hoping to open it as a museum dedicated to agriculture and its most famous resident.” When the Civil War ended in 1865, communities countrywide began clamoring for parks to be built. He explained, “Communities wanted their ‘Central Park.’ It was like a dam bursting. The natural team to turn to was Olmsted & Vaux, and they produced a series of masterpieces across the country. Their sophomore initiative was Prospect Park.”

When the Civil War ended in 1865, communities countrywide began clamoring for parks to be built. He explained, “Communities wanted their ‘Central Park.’ It was like a dam bursting. The natural team to turn to was Olmsted & Vaux, and they produced a series of masterpieces across the country. Their sophomore initiative was Prospect Park.”

“The Enchanted Gardens – Coolest and most delightful spot on Long Island” read a 1924 ad featuring couples in elegant attire, dining with tablecloths and dancing under a forested scene. At the time, M. Lawrence Meade was the Forest Hills Inn general manager. Special buffet lunches were served from 12 to 2:30 during tournaments, as the inn had its own tennis courts, accessible through a long-gone landscaped arched entryway from the Tea Garden, predating the Forest Hills Inn Apartments annex at 20 Continental Avenue. The inn was open for dinner daily, and dancing was held on Wednesday and Saturday evenings with no cover charge.

“The Enchanted Gardens – Coolest and most delightful spot on Long Island” read a 1924 ad featuring couples in elegant attire, dining with tablecloths and dancing under a forested scene. At the time, M. Lawrence Meade was the Forest Hills Inn general manager. Special buffet lunches were served from 12 to 2:30 during tournaments, as the inn had its own tennis courts, accessible through a long-gone landscaped arched entryway from the Tea Garden, predating the Forest Hills Inn Apartments annex at 20 Continental Avenue. The inn was open for dinner daily, and dancing was held on Wednesday and Saturday evenings with no cover charge.

The Better Living pavilion seemed pretty lame, but they had a number of free samples, including a new grapefruit soda, “Wink.” Then I went to Bell Telephone for a tour through communications history, “From Drumbeat to Telestar,” and to beep away at the many new models of push button phones and, a real treat in pre-video game days, to play electronic tic-tac-toe against a computer.

The Better Living pavilion seemed pretty lame, but they had a number of free samples, including a new grapefruit soda, “Wink.” Then I went to Bell Telephone for a tour through communications history, “From Drumbeat to Telestar,” and to beep away at the many new models of push button phones and, a real treat in pre-video game days, to play electronic tic-tac-toe against a computer. And although this was my 14th visit, the exhibits were still captivating, although far from realistic as it turned out. The only thing they got right was lunar exploration, then just four years away. But they overplayed their hand by including things like regular commuter spaceship landings. There are still no farms in the desert or underwater vacation resorts, or weather stations beneath the Antarctic ice. And predictions for the City of Tomorrow, a tomorrow already long in the past, seemed to have been based less upon science or urban planning than on viewing episodes of The Jetsons. There are no roadways in the sky, high speed buses, or underground freight conveyor belts. And the only times I’ve been on moving sidewalks have been at airports, and, ironically, at Freedomland in the Bronx in 1962. But, accurate or otherwise, it was all great fun. And like so many other things at The Fair, it did much to warm my 13-year-old heart.

And although this was my 14th visit, the exhibits were still captivating, although far from realistic as it turned out. The only thing they got right was lunar exploration, then just four years away. But they overplayed their hand by including things like regular commuter spaceship landings. There are still no farms in the desert or underwater vacation resorts, or weather stations beneath the Antarctic ice. And predictions for the City of Tomorrow, a tomorrow already long in the past, seemed to have been based less upon science or urban planning than on viewing episodes of The Jetsons. There are no roadways in the sky, high speed buses, or underground freight conveyor belts. And the only times I’ve been on moving sidewalks have been at airports, and, ironically, at Freedomland in the Bronx in 1962. But, accurate or otherwise, it was all great fun. And like so many other things at The Fair, it did much to warm my 13-year-old heart.